Mapping The Car – Anti-Squat

If you want to get somewhere it helps to know where you are starting from. Even if you are not sure where you want to go.

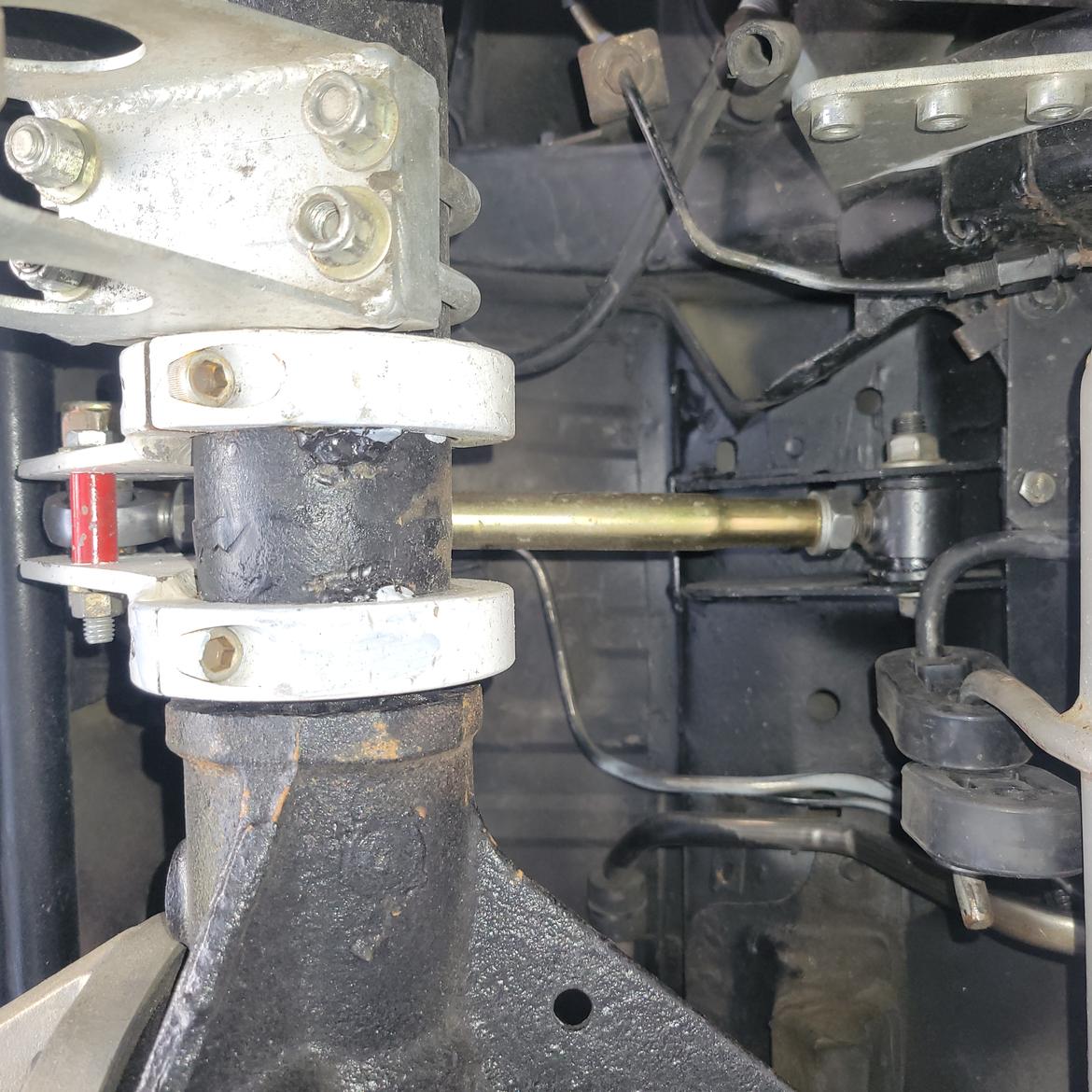

Back in 2015 I reworked the OEM rear suspension to something based on the Steeda Kit for this car. “Something based” are the operative words. Designed from photos online and some engineering knowledge. I think I was on a good track until I was assembling the thing and realized the upper towers would not fit with the MM panhard.

The Steeda panhard is simpler than the MM because it is intended to be welded in and has no cross bracing from one side to the other. I expect they intend for you to add cross bracing elsewhere. It is a nice clean design.

The MM panhard is intended to be bolted to the frame (you can also weld if for greater strength). It has two tubes running behind the attachment points that tie one side of the frame to the other. Loads are distributed into both sides of the car. Very strong, perhaps a little heavier (my guess). It is a bulletproof design.

I was not willing to start butchering the panhard framing so I basterdized the design by tipping the upper towers forward, shortened them, and shortened the upper links.

I did not know where I was so I did not know where I was going. Even so, I ended up in a better place (wherever it was) and the car handled better. Something about blind squirrels and nuts comes to mind.

Ten years and an additional 200 HP later I am now willing to basterdize the MM panhard and create something more/better based on the Steeda design. And this time I will know where I am starting from.

First step; buy a LASER level. You can have a reasonable one now for about $35.

These things are self-leveling and put out a bright LASER cross hair to use as a reference.

Second, get the car safely in the air and level on its suspension as if it were sitting on perfectly level ground. This is fussy and iterative and took about two days work even with a lift.

The front was sitting on the support frames and alignment stands I made some years ago. The axle was on the shortened HF stands also from some years ago. Car is supported on its suspension and dead level (as measured from the wheel centers to the laser beam). In my case I was able to set the LASER exactly at the elevation the ground would be including tire deflection. If the exact elevation can’t be set then you can just do math and add or subtract the difference.

I found the actual centerline of the car in a couple of steps:

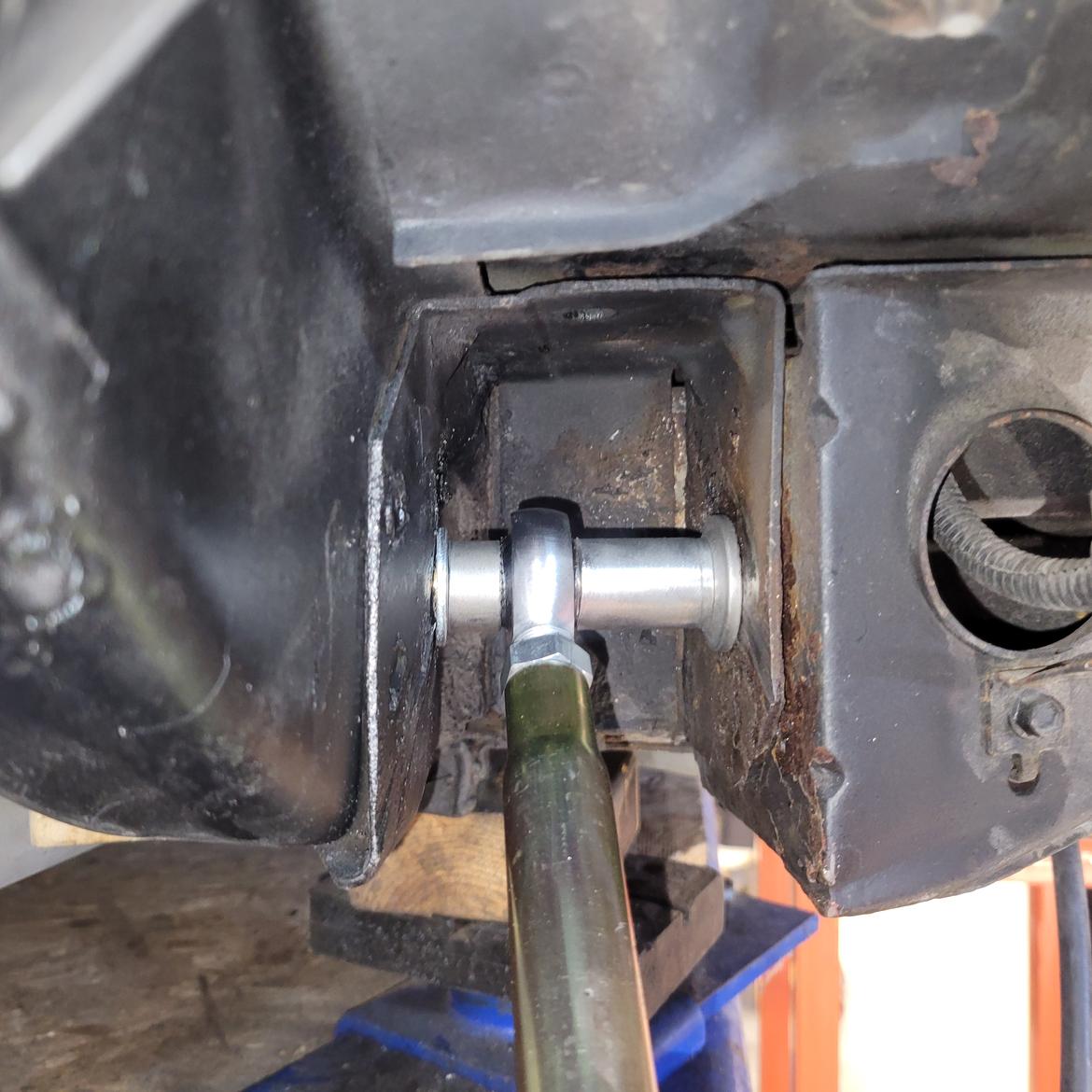

At the rear I used a length of wood quarter round poked through the suspension. Marked it at the rotors. Took it out, measured and marked the midpoint, put it back and hung a plumb bob. Photo below shows the string tied to a magnet as an example.

I did a similar operation at the front but since it was on the alignment stands I used the two tape measures that are for measuring tow in.

Once the center was found I marked it on the bottom of the car in a few places so the vertical laser line could be set on it.

Look closely and you can see the green laser on the paint mark at the K-member running all the way to the cross hair on the garage door.

Other general measurements needed are the exact wheelbase of the car. Tire rolling radius (with deflection), vehicle CG height, vehicle mass (with driver), Front and rear suspension un-sprung mass.

Vehicle CG height I used from my books for this car at 16”. I have the steel to fabricate some corner scales which will give me the actual CG but was sick last winter and did not get to them. That project will come after this season.

The vehicle weight I have from earlier readings on a commercial scale (truck stop). It will do for now.

Un-sprung mass:

For the front I weighed the tires (49 pounds each) and estimated ½ the weight of the MM control arms & springs. I was able to weigh some old rotors and calipers.

Front weight came to ~125 pounds each side or 250 pounds total.

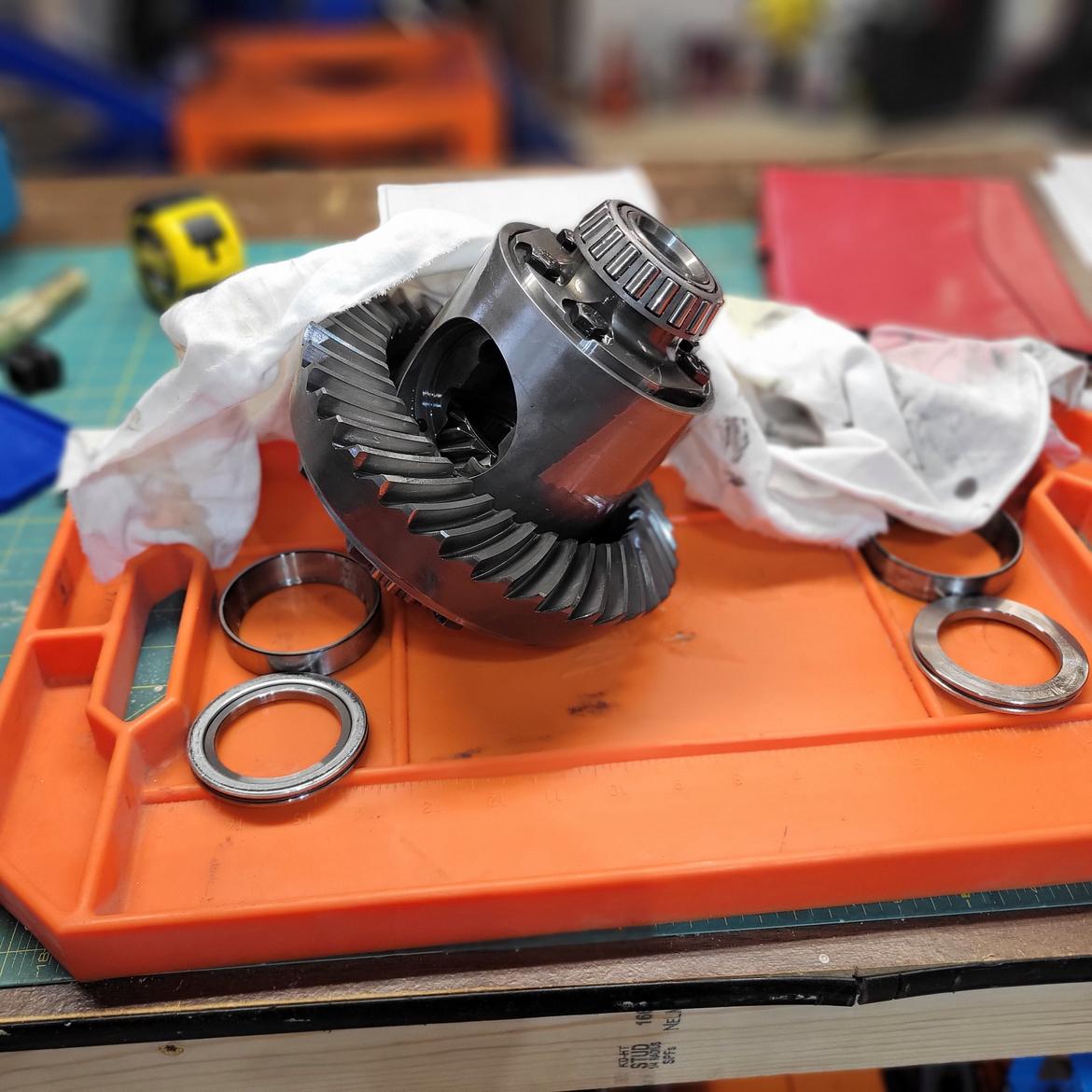

For the rear I used a historical weight of 160 pounds for the axle assembly, added the brakes tires etc. and came to a total of 410 pounds. Regretfully I forgot to check this when the axle was off the car (sigh).

All of this data was entered into a spreadsheet downloaded from Crawlpedia at:

https://www.crawlpedia.com/4_link_suspension.htm

This is a rock crawler website but has a spreadsheet you can download to calculate rear suspension geometry. It is old but it works. The only problem is I have a five-link suspension (the panhard) so the spreadsheet did not calculate the rear roll center height properly.

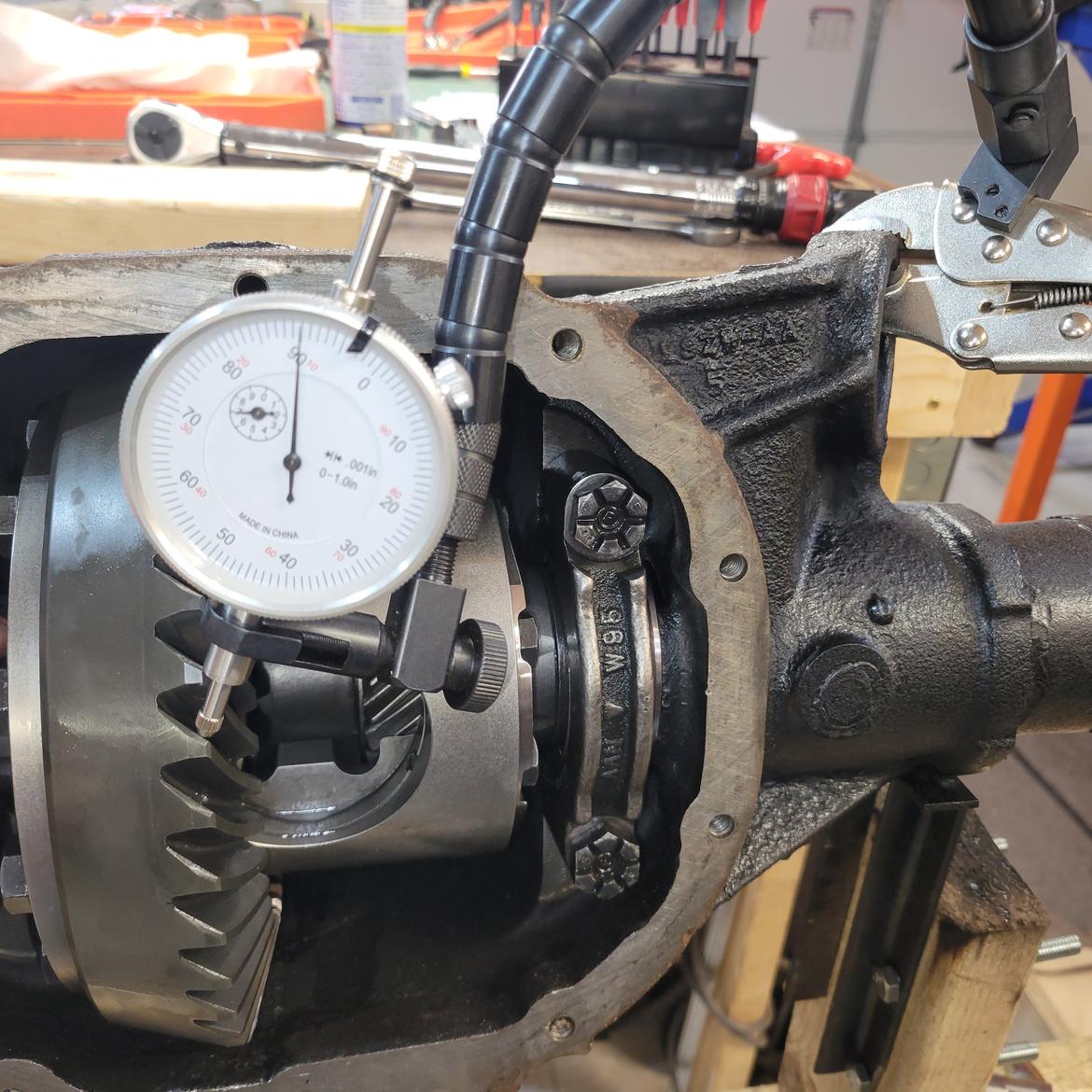

For a four-link suspension such as the OEM design the spreadsheet calculated the roll center height at about 16”. This is correct. However, with the panhard the roll center is the height of the panhard where it crosses the centerline of the car. In my case this is directly measured off the laser at 6.875”. I simply over-road the formula in that cell (C33 on the VectorCalculations tab) to show the correct value even though the calculation is not used elsewhere.

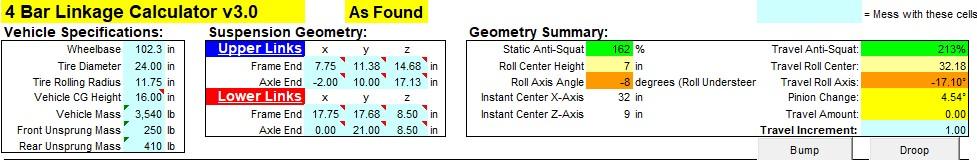

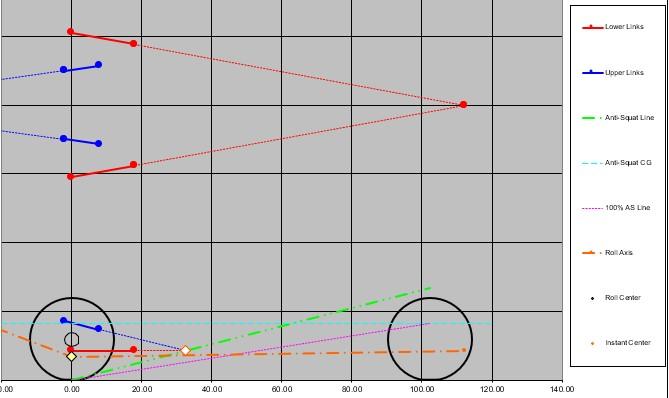

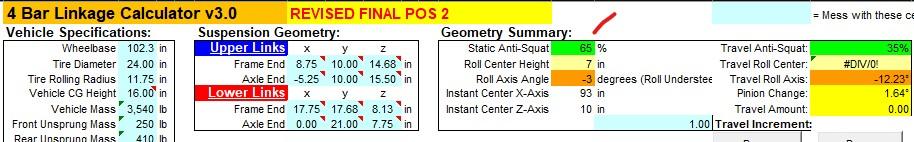

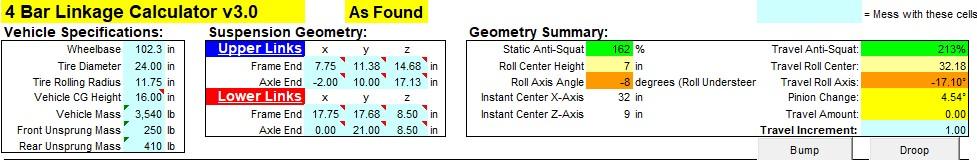

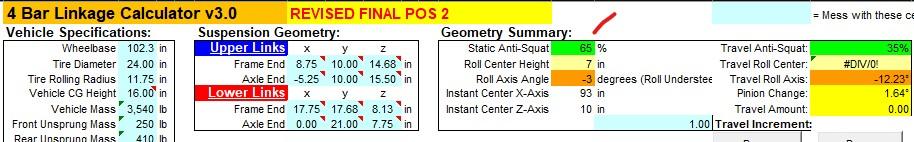

With all this data entered into the spreadsheet my existing suspension looked like this:

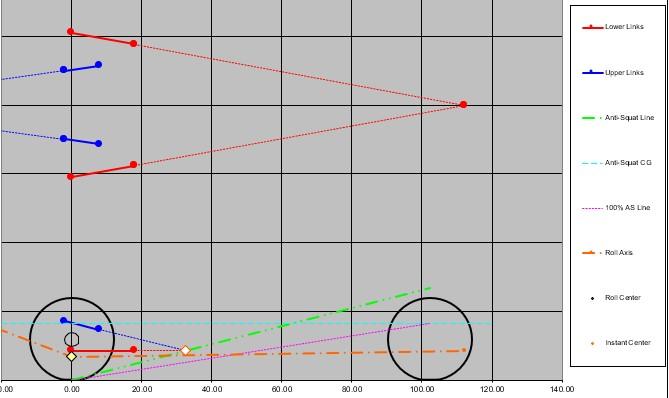

The graphics of the rear suspension are below. Top View is above and Side View below it.

The big surprise was the 162% calculated anti-squat in the center green cell on the top image. That is what you might set up for a drag car.

For reference, the OEM design has an anti-squat of about 60%. The Steeda design probably puts it up around 80% (my guess).

Here is the problem: Anti-squat forces the rear frame of the car UP under acceleration load. Pushing the rear up must push the tires down. As soon as the car starts to accelerate it increases load (more than just weight shift) on the rear tires because it is also raising the rear. Great for drag racing up to a point (too much and you are raising the car instead of pushing it forward - The lift has to balance with the traction).

Great for an angle winder but only up to a lesser point: When you let off the gas and stop accelerating the additional load on the rear tires instantly goes away. This is just as it enters a turn. The unloading of the rear tires can now help cause a spin out. For a Road Track car the books say you should not go above 50%. Or 80%. There is some disagreement.

For an autocross car I suspect these numbers may be conservative. The autocross car is not being set up for long smooth max G cornering. It is constantly in transition. I think a better number to shoot for might be about 100%. But my last name is not Andretti so we will see. I built some adjustment into the final upper link design (more on that later).

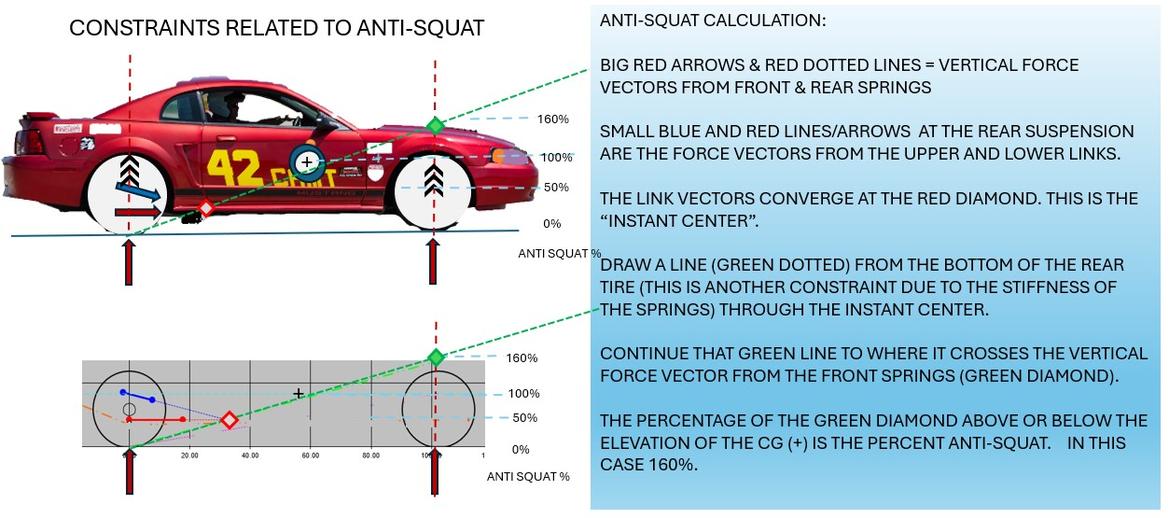

Anti-Squat Explained

What is this “anti-squat” you speak of?

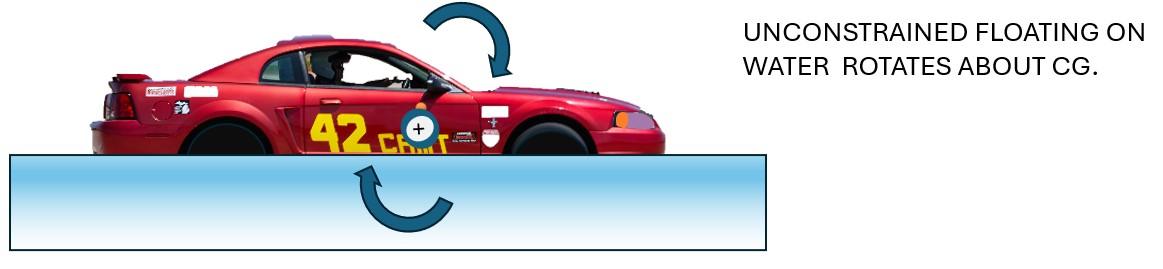

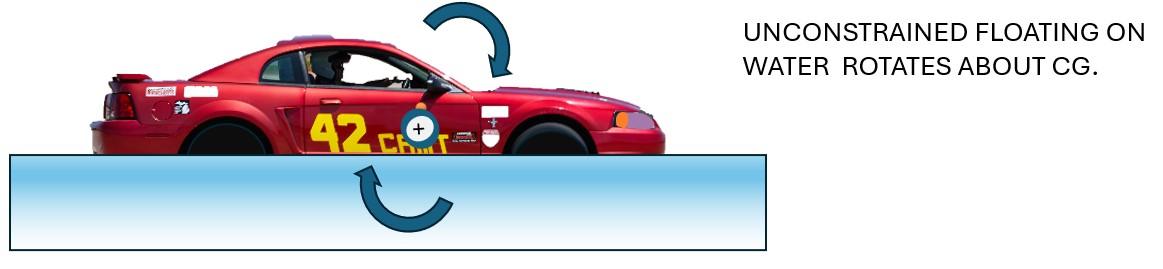

Start with the Center of Gravity (CG). It is the balance point of the car in all three dimensions with NO CONSTRAINTS on it. Fling your car into the air (or use a stick). It rotates about a single point while airborne. That point is the CG.

There are less destructive ways of finding the CG but that is for another time and this description helps with the discussion that follows.

We tend to think of our cars as solid objects, but they are not. Think of your car without the wheels and axles “floating” like a boat on its springs (almost like flying through the air).

The car boat rocks in the water fore and aft about its center of gravity (16’ above the water and 42 inches behind the front springs in this case).

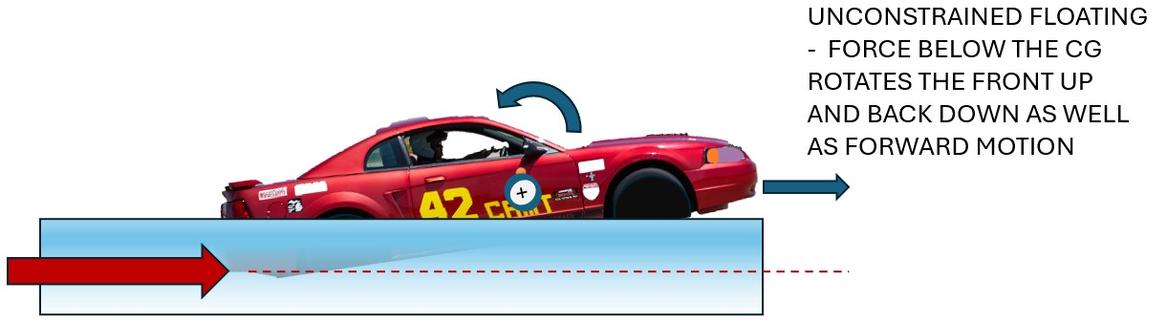

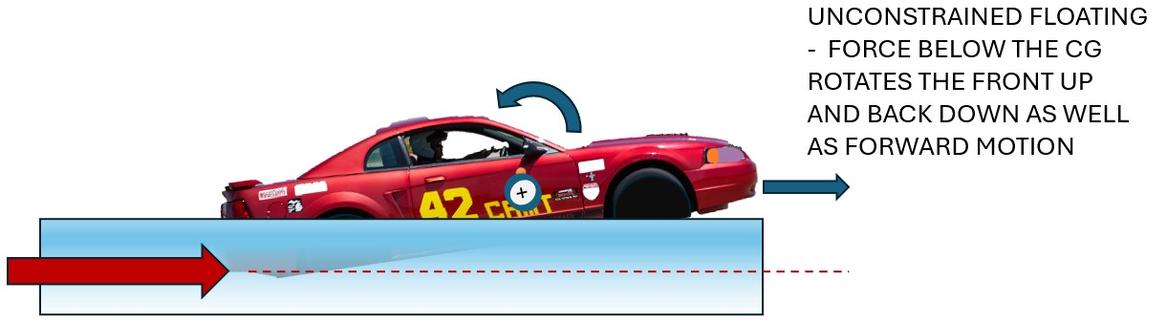

If I push the car forward down low from the back in a horizontal line (where the axle would be) you can imagine it tipping up in the front and down in the back as it accelerates (like a normal small boat with an outboard motor). This is because the thrust vector (red dotted line below) is aimed below the CG.

What if I tip that outboard motor so that it is not pushing horizontally? The thrust vector is pushing up at a steep angle as well as forward. If the angle is steep enough (pointed above the CG) the back of my car/boat will raise when it is accelerating (and nosedive into the water and sink. Not recommended. Roll the windows up).

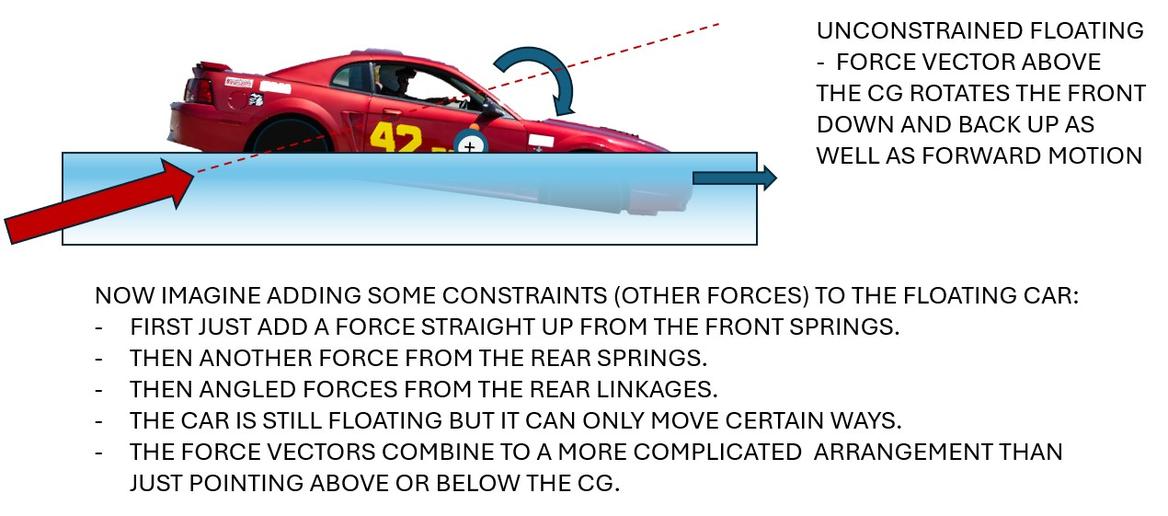

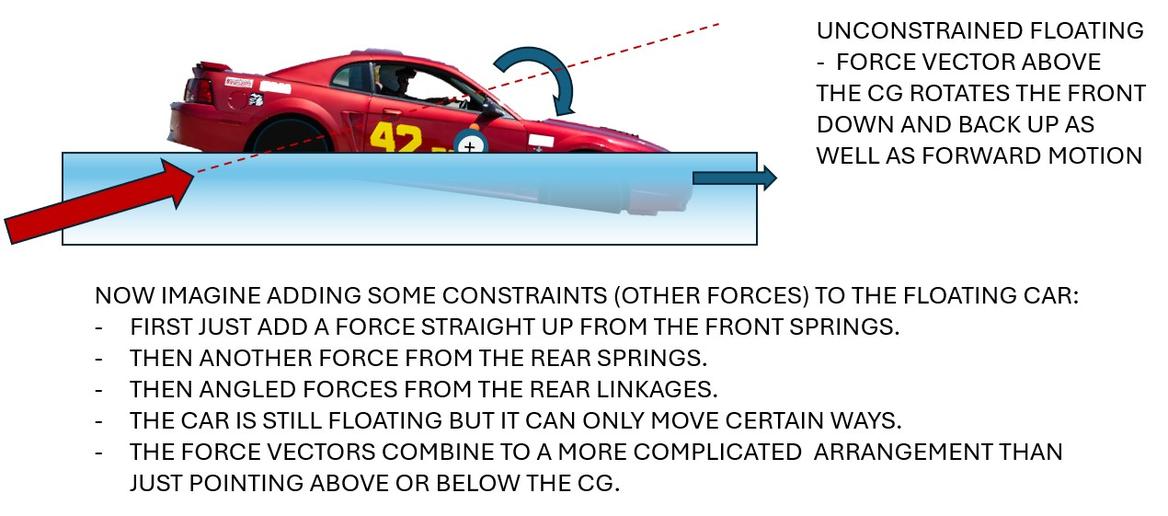

The above is over simplified but not a bad analogy. Your car IS sort of floating on its springs but its rocking motions are “constrained” by suspension linkages connecting it to the ground.

The tires touching the ground are a major constraint, but those forces are “filtered” or “translated” through the suspension linkages and springs (The car is not a solid object).

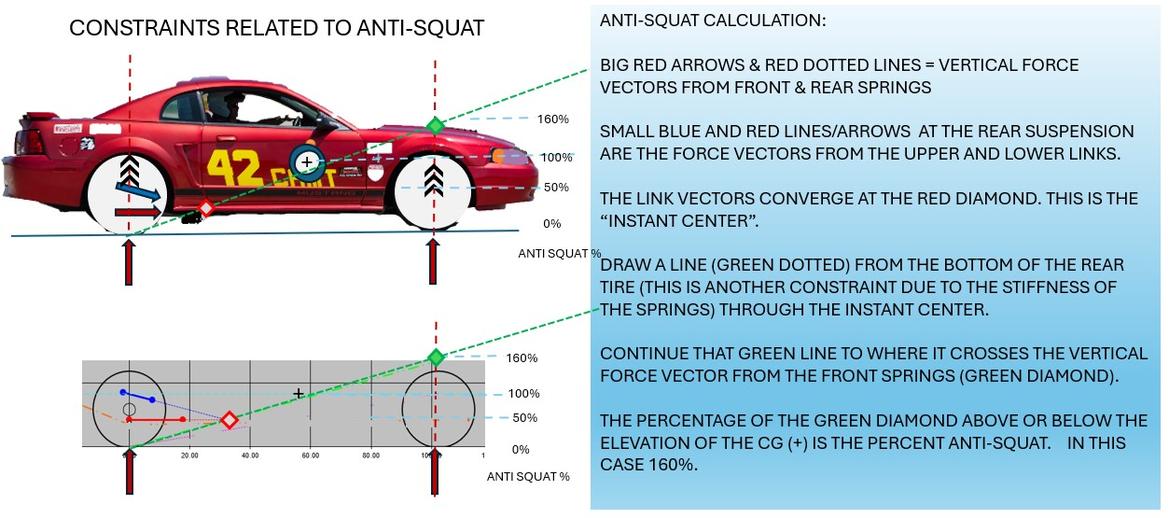

The actual geometry of how the rear suspension behaves under acceleration is below. This is the same chart from the spreadsheet (above) annotated to show what the anti-squat calculation is doing. Follow through the steps on the right and keep in mind the floating car discussion.

Note that the green diamond showing where the force vector from the rear tires (as filtered through the suspension) intersects the vector pointing up from the front spring is about 160% of the elevation of the CG. So this suspension (as found) jacks up the rear of the car on acceleration. Great for drag racers.

I have gone back and looked at videos of the car from inside and out and I can see it happen but not as pronounced as expected. I suspect that is because I am not running on drag radials on a prepared surface.

I also have had spinouts, on occasion, that seem to be related to lifting the throttle while at max cornering loads… Hmmm…

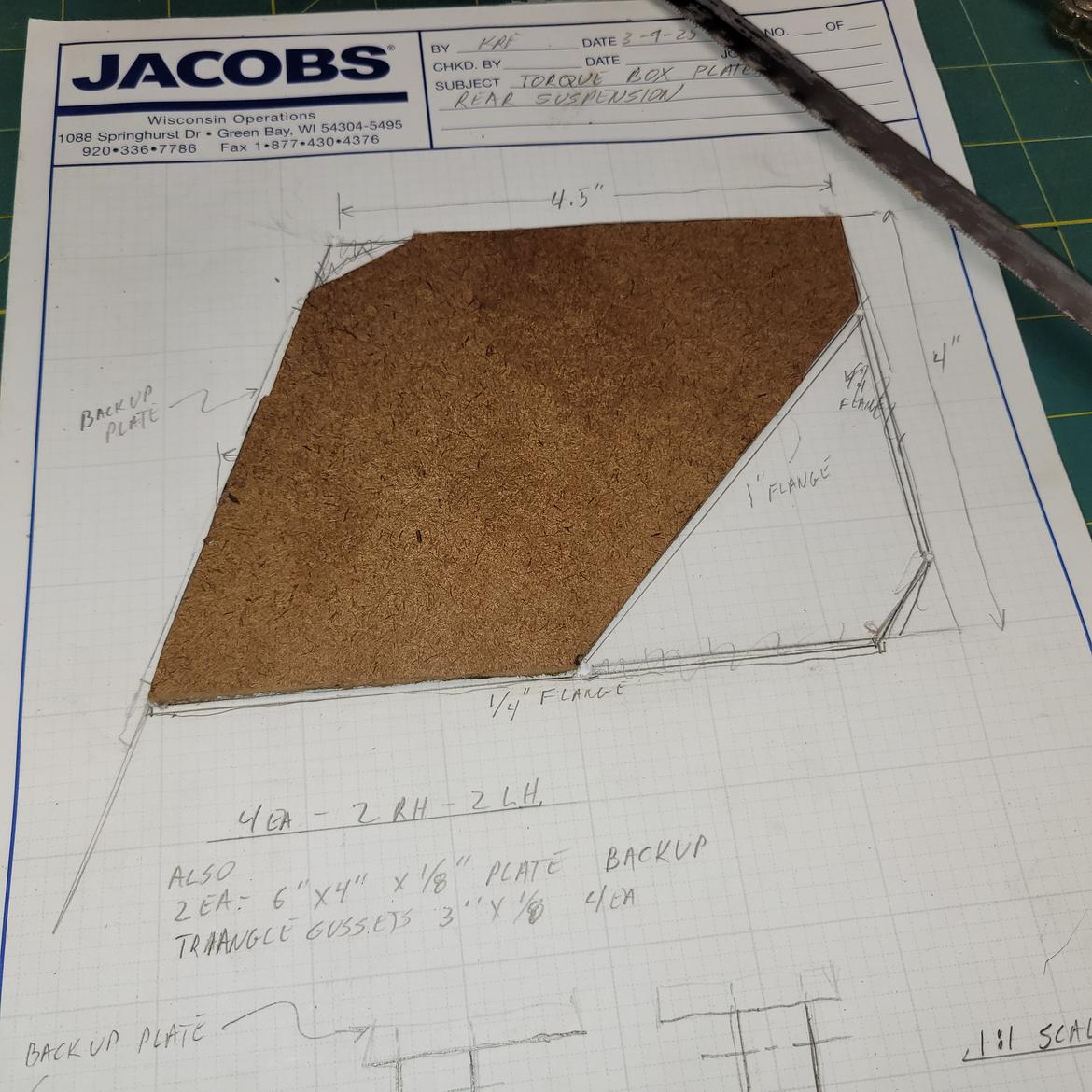

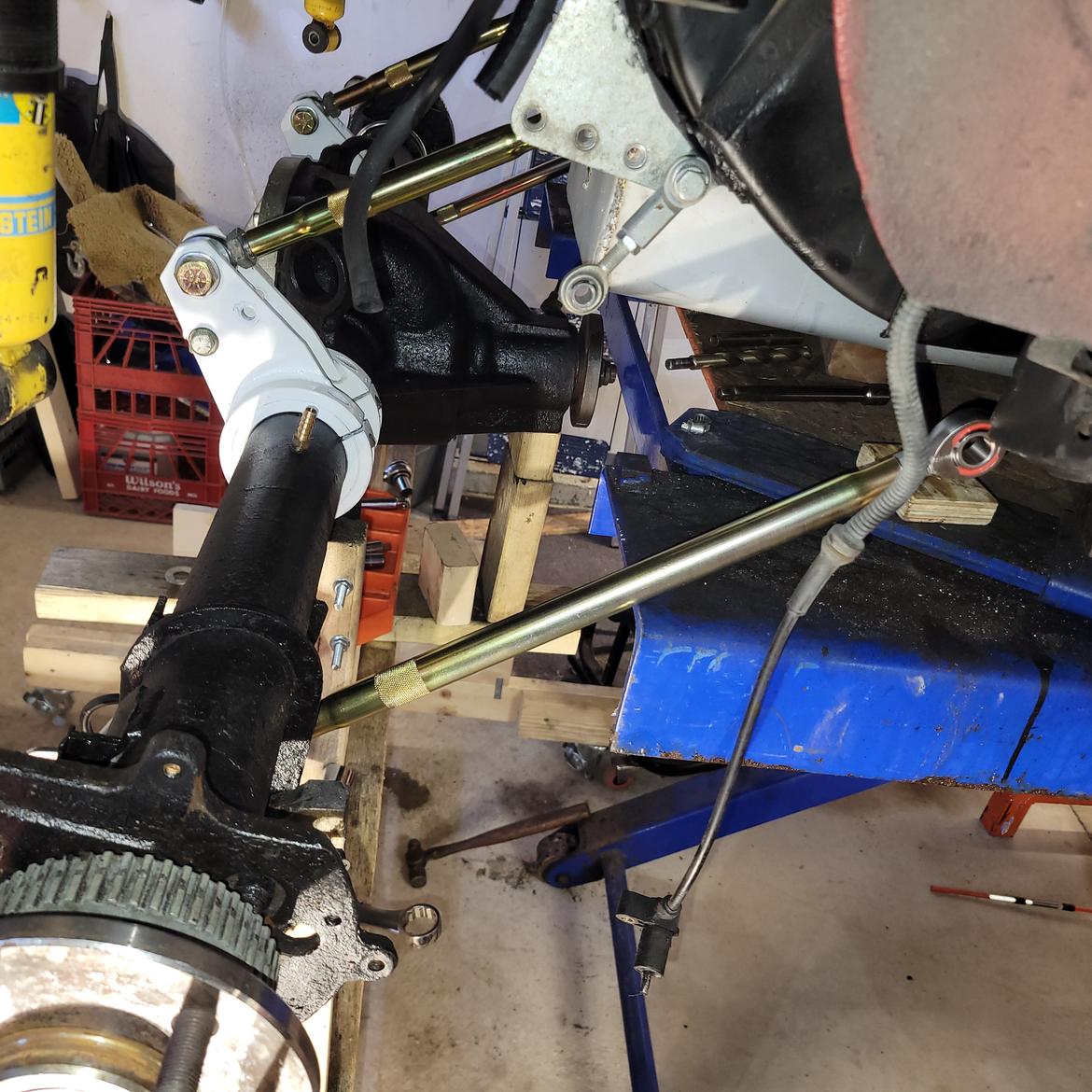

The new geometry, shown below, looks about the same but is currently set for 65%. I built multiple holes for the upper links into the frame of the car. The next one down will make the anti-squat about 100%. Testing is underway…

The geometry and angles of the links can make a significant difference on how the car behaves. Just a ½” elevation difference in the upper rear links at the frame makes a 40% difference in the anti-squat.

That is why I screwed up the geometry 10 years ago not following the Steeda design more closely.

That is why simply lowering your car can have a profound effect on handling (in a bad way). Lowering changes the angles of the linkages & constraints. You can never change just one thing – other things will change as well.

That is why the upper link towers lean so far back requiring the upper links to be twice as long as they could have been. The longer the links the less the angles change when the car goes over a bump or leans in a corner.

If you have trouble visualizing that: Imagine the upper and lower links were ten feet long and the axle goes over a two-inch bump. The link angles hardly change. Imagine the links were 6 inches long and the same bump. Big geometry change. It is all about the angles.

The above discussion is limited to Anti-Squat. But exactly the same relationships apply to all the suspension dynamics for stopping (anti-dive) and cornering:

Floating car --> Add force vectors/constraints --> instant centers -> New composite force vectors... All filtering the inputs from the ground into the frame of the car.

With some effort most people can wrap their heads around one part of it at a time (like anti-squat). All together this gets wildly complicated (I'm maxed out).

Yet they designed this OEM suspension in the late ‘70s with slide rules, base function calculators, and protractors on drafting tables. That is dammed impressive.