Cut the Chitchat

Yes, a huge part of the appeal of autocross is the social aspect. Hanging out with car-loving friends on a sunny weekend may be one of the most enjoyable aspects of the sport, but you’re going to have to take a break from your pals for at least one course walk.

The goal here is to get a look at the complete course without having to constantly switch gears. Ideally you want to take multiple distraction-free strolls, but we all know the reality here: If you get in one walk without chatting with a pal or petting a cute dog or taking a phone call or answering a text, you’re pretty lucky.

If you do run into a distraction, or a chatty friend, stop walking, because the last thing you need to do is cover distance while your brain is somewhere else. Pause the walk while you deal with your other business, then return to the course walk when you can devote your full attention to it.

Learn in Chunks

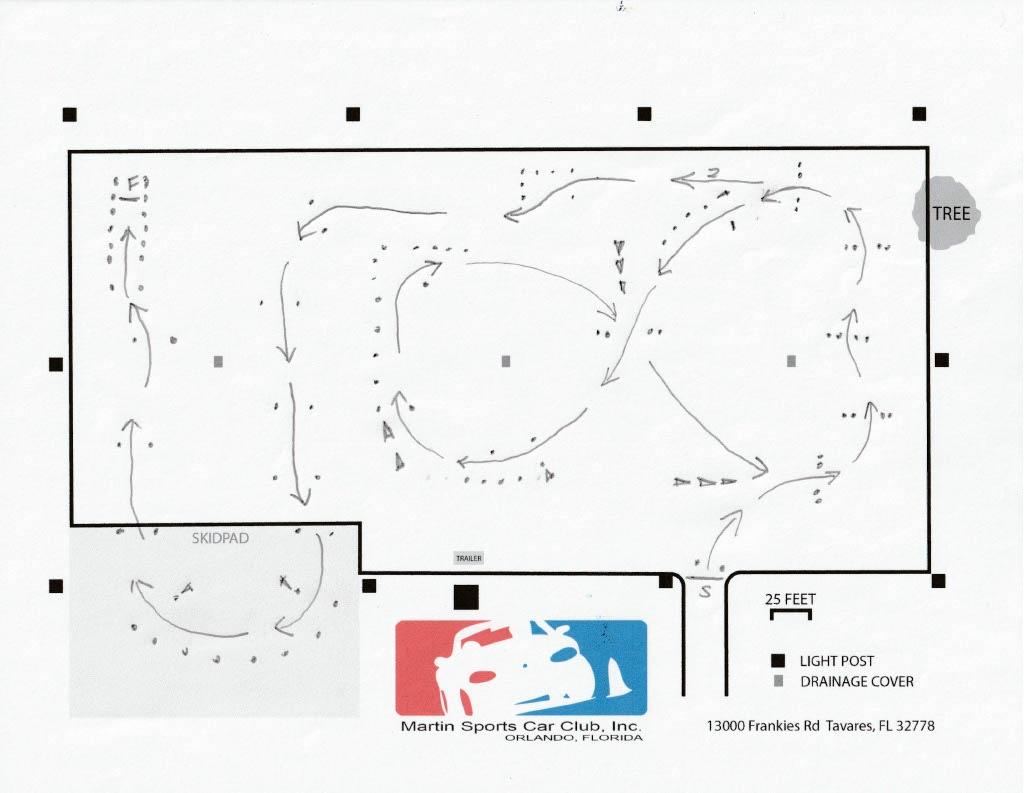

We find that a good way to learn an autocross course is to progressively build the memory in your brain. Just like your old Simon game started you out with one light, then two, then three, making it easier to progress to the final multiple-light sequence, the same progression works for learning autocross courses, especially complex ones.

What this looks like in practice is walking a small section of the course and finding a natural “rest” point–maybe a straightaway or another section where your eyes can shift farther ahead. Take a short pause and then mentally drive the course to that point.

A couple hundred yards later, pause again and mentally drive all the sections you’ve learned to that point. We find that stacking smaller sections on top of each other in your brain is a better way to learn longer, more challenging courses than trying to internalize the entire thing at once.

When you’re done–and it may take multiple walks to get to this point–you should be able to drive the entire course in your head, from start to finish, meaning you’ll have few, if any, surprises on your first real lap. We’ve known top drivers who could close their eyes, start a stopwatch, and mentally drive a lap within tenths of a second of their actual lap time. If this is you, congratulations, you’re a total mindfreak, but you also possess a valuable skill that can lead to great autocross success.

The Eyes Have It

Vision is your primary weapon in an autocross situation. Whoever gets their eyes in the right place at the right time is going to have an advantage when it comes to getting through the cones the quickest.

But think about where your eyes are when you’re walking versus where they are when you’re in the car. Depending on how tall you are and what you’re driving, you could have a 2- or even 3-foot vertical difference.

Get those eyes to car level as much as possible during a walk, particularly at and when approaching corner entries. This also applies when entering complex sections where you’re looking for exits early in a maneuver.

[Look Ahead: You’ve heard it plenty, but what does it really mean?]

Also remember where your eyes are going to be relative to the outside boundaries of a course. We frequently want to walk an “ideal” line, maximizing our turning radius, closely clipping apexes and using every inch of the road on the exit. But your eyes are never going to be any closer to cones on your right than one car width, and they won’t be any closer to cones on your left than one door width.

Keep this in mind when you’re walking and build your sight pictures as they’ll actually be viewed from the car, not in your idealized world where your car is only as wide as your shoes.

Don’t Look Back

This one might be a hot take, but we’re also going to suggest you never look backward during your course walk.

Yes, you can make an argument that you may see a line or a spatial arrangement of maneuvers by looking backward that you didn’t see while looking forward, but we’re going to say those are edge cases and not typical.

In general, you don’t want to be crowding your brain with visual data that you don’t need. Concentrate on getting a true preview of the course, not trying to find Easter eggs in the design by viewing it from various angles. In the car, you’re only going to approach it from one direction, so that needs to be your primary focus.

This is a tricky concept to explain in words, but an autocross course will drive closer to how it “feels” than to how it measures out. What this means in practice is that the visual data you get through the windshield will most closely match how you actually attack the course than the mathematical details of the particular maneuver.

Good course designers will use that match to create situations that will have certain characteristics, but you only ever REALLY know how a course is going to behave once it’s on the actual pavement. Maybe there’s an expansion strip, or a frost heave, or some background complexities that make the view through a certain section look different than it does on paper from above.

Trust your eyes the most–and trusting your eyes means not giving them information they don’t need, like what the slalom looks like from the other direction.

Pause and Review

Multiple walks are usually a good idea, but as when taking multiple runs, each subsequent walk after your first is more valuable if you approach it with a plan.

Can you mentally drive the course in its entirety? If so, then focus on fine-tuning your approach, or finding areas that might be “traps” for carrying too much momentum, or identifying areas that may drive narrower than they look.

Remember, you can turn a lot quicker over less distance in a pair of Adidas than you can in a Camaro, and 3600 pounds of car has more inertia than you and whatever you have in your pockets. Once you learn the course, concentrate on trying to identify these spots.

If you don’t know the course after your first walk, that needs to be your primary goal on any subsequent walks. Microanalyzing a certain section will never gain you as much as not knowing a particular section will lose you, so committing the course to memory should be your top priority before trying to agonize over particular segments.

Find seconds, then tenths, then hundredths.