Photography by Chris Tropea unless otherwise credited; Lead by Tom Suddard

We’d never been closer to winning a Lucky Dog endurance race in our V6-swapped Miata. We finally had a fast car–the fastest car, if our best lap from our last race was to be believed–but we were stopping to refuel twice as often as the competition.

[Three engines later, our V6 Miata finally finished an endurance race]

All the blood, sweat, tears and blown engines would be worth it if we could just figure out how to make our car run longer than 45 minutes on a tank of fuel.

Photograph by Tom Suddard

So, how do we make that happen? Sadly, there were no easy answers.

“Drive slower” wasn’t realistic, as we could probably eke out only another 5 to 10 minutes on a stint by backing off the throttle.

We needed to stay out twice as long.

Lowering the car’s aerodynamic or mechanical drag meant slowing it down, too. Plus, again, that might be worth single-digit percentage points when we needed a massive improvement. Our only real option was to (drastically) increase the car’s fuel capacity.

Early Miatas like ours are fantastic endurance racing cars, except for their Achilles’ heel: that tiny, tiny stock fuel tank.

Early cars held just 11.9 gallons of fuel, while later 1.8-liter cars like ours came with “big” tanks holding 12.7.

Neither was anywhere close to enough for our thirsty 300-horsepower V6. Adding insult to injury, we couldn’t use all the fuel in our tank, either: Even with a Holley HydraMat, our car fuel-starved with a few gallons still left in the tank.

So, how could we carry more fuel? Simple: Install a bigger tank.

But that’s easier said than done in a Miata, where the OEM tank has a convoluted shape squeezed into the space between the rear subframe, spare tire well and package tray.

Installing a normal square fuel cell would mean major packaging and safety compromises, either putting the weight (and the danger) so high up it blocks the rearview mirror, or so far back it resides entirely in the trunk’s fragile crumple zone.

Neither option was appealing. And while Lucky Dog allows us to install big auxiliary tanks that supplement the stock parts, one would still require major packaging and safety compromises. Plus, we figured it would cost nearly $2000 to safely add a few extra gallons while retaining our stock tank, and it still wouldn’t be any safer.

We didn’t want to screw around or do this job twice. Instead, we wanted a custom-built fuel cell designed for our car–something that would require minimal compromises, bolt right in and add significant capacity to our car.

Oh, and did we mention the desire to add safety, too? While a stock Miata’s tank is pretty safe–credit to its well-protected location–it’s nothing compared to a real SFI cell with a puncture-proof bladder. If we were going to turn our Miata into a rolling bomb, we’d at least like it to be hard to set off.

We knew what we wanted. Now we needed to figure out how to get it.

A fuel cell has a few major components: a metal can, some hardware to mount it in the car, and the SFI-rated bladder that goes inside it all.

We could probably figure out the first two steps, but we had no idea what went into bladder building–or what concessions we’d need to make to our design to make a cell that ultimately worked. We needed help before we wasted a lot of time and money.

So we walked the halls of the PRI Show, chatting with companies and eventually meeting one we’d never even heard of: Schultz Engineered Products, helmed by a circle track racer named Rob Schultz.

Could circle track people really understand something as complicated as a car with double wishbones front and rear? Could they handle a race car built with sheet metal instead of tubes? And could they really build us a big, safe cell?

We’ll be perfectly honest: We were skeptical. But the company’s work spoke for itself, and we saw beautiful cells on display. We also saw video of massive racing incidents where their cells stayed intact. “Okay, maybe we should come over and visit,” we said. “Where in this big ol’ country are you located?”

“Oh, we’re about 45 minutes south of your shop.”

Looks like we’d found our experts!

Everyone loves a good factory tour, so Schultz Engineered Products was our first stop after we got home from the show.

True to their word, the folks there really did have a factory churning out fuel cells, along with parts for NASCAR and the aerospace industry. There’s a second location up in New Jersey, too. And while Rob and his marketing manager, Dale, seemed to be new to our niche of racing, they’re veteran participants in the circle track and off-road worlds who clearly understood what we were going for.

So we hatched a plan: We’d remove the Miata’s stock tank and 3D scan it. Then, we’d trim the chassis where reasonable and scan the resulting hole.

Next, Schultz Engineered Products would build a foam mock-up cell to check its work before finally going to production, building a real, SFI-approved fuel cell that bolts into the factory mounts and greatly increases safety and capacity.

Then, as the cherry on top, the company would do a production run and add it to its catalog. That means anyone would be able to buy the exact setup we’re running in our car.

If this worked, we wouldn’t just make our Miata competitive: We’d democratize our custom fuel cell and make this platform a more viable endurance racing effort for everyone else, too. Plus, we’d get a cool story about the process.

We penciled “scanning day” onto our calendar, yanked the car’s rear subframe out of the way, then watched as Rob showed up in a crisp polo shirt, opened up his gaming PC, and waved a $6000 Peel 3 scanner around the car and then around its stock tank. Slowly, the car appeared in the computer in a ritual that looked less like building a race car and more like building a spaceship.

Photograph by Tom Suddard

Which is why we were shocked when Rob asked if he could borrow an air saw “or a Sawzall, I guess.”

Turns out he likes getting his hands dirty, too–and it was already time to face the unfortunate reality of adding fuel capacity: We would definitely, absolutely, be cutting up the car.

The stock tank already uses the factory space completely, so to add capacity, we’d need to grow in at least one direction.

But which one? After looking over the car and taking some measurements, we planned our cuts: We’d basically cut a rectangular hole straight up from the stock tank, leaving the car’s frame, stock tank mounts and double-walled body reinforcements intact but removing the spare tire well and the sheet metal tank cover.

This would let our new tank grow up a few inches taller than stock. We chose this plan because we felt it was the best combination of ease of manufacturability, installation, safety and capacity–and because it would be easy for our readers to replicate on their own cars with ordinary skills and tools. The final cell would look like the bottom half of the complicated Miata tank attached to a big, square top half.

An hour later, we had a pile of sheet metal on the ground, and Rob was again waving his scanner around. Then he packed up the scanner, got in his car and went back to his factory to start drawing our virtual fuel cell.

Though the heavy lifting happened in the computer, Rob wanted to do an old-school test, too: putting foam blocks in the car to make sure the computer matches reality.

He brought an assortment of foam blocks representing different capacities, cut to roughly the shape and size of the finished cell, and had us sit in the car to test run them.

Does that extra gallon interfere with the cage? Will this filler neck block the mirror? Can the final tank actually be installed and removed without fouling on some other part of the car?

After a few tests and some minor trimming, we’d chosen our favorite design from the menu, so Rob scanned everything again and sent the final designs to production.

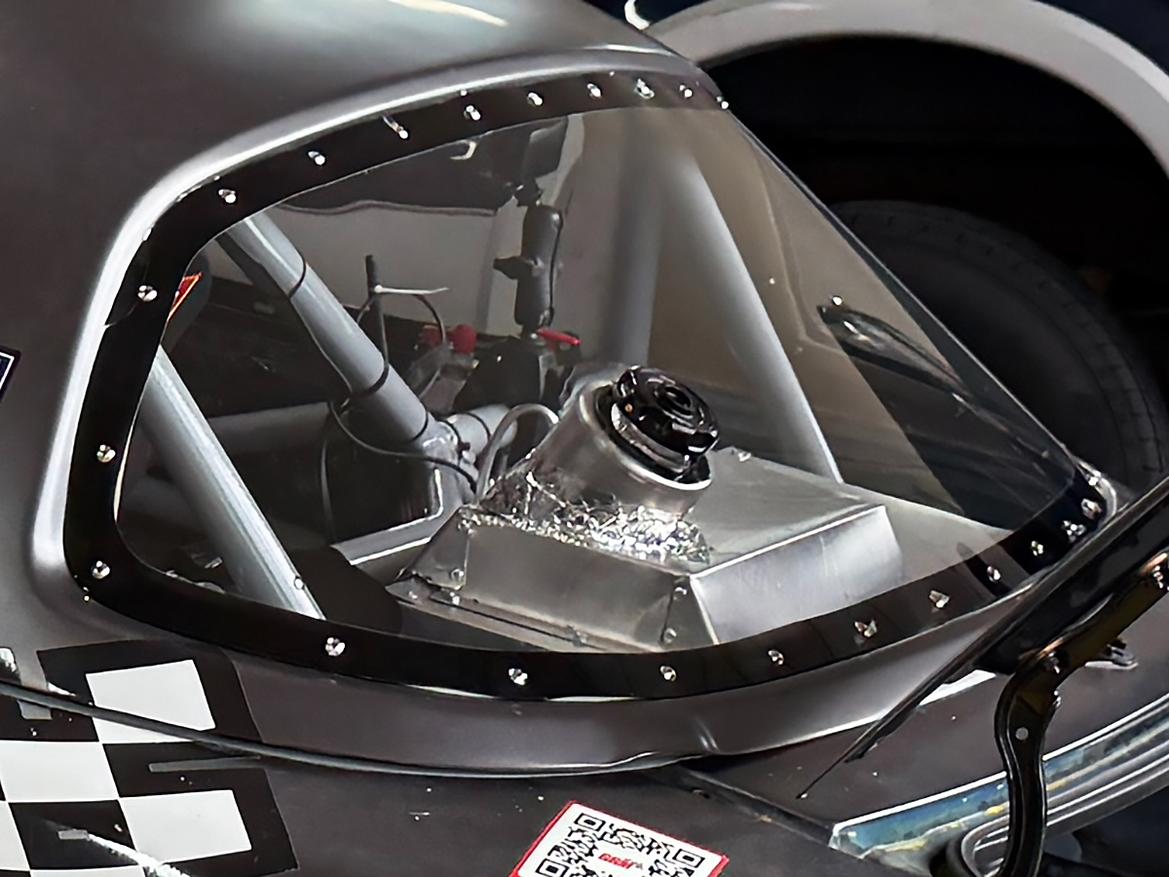

The final design is composed of three key parts: a steel frame that supports the tank and bolts directly to the OEM tank mounts; an aluminum tank that holds the bladder; and an SFI-approved, ultrasonically welded, custom, fire-retardant bladder that goes inside the can and holds the fuel.

This bladder contains an internal pump sitting in a sump with trap doors to ensure we can use every last drop of fuel, and it’s filled with foam to keep fuel from sloshing around, too. The whole contraption is CNC-cut and bent, meaning while our tank is a prototype without the normal powder coating and graphics of a Schultz cell, it’s not some one-off science project. It’s a real product ready to go into production.

But would it fit in the car? Good question, and one we desperately needed to answer as our next race date approached.

But then, well, we all got busy–Rob with paying customers and winning his own races, and us with our summer travel schedule and our other projects.

These side quests melded with Schultz’s prototyping workflow (our tank made trips back and forth from Florida to New Jersey as various parts were designed and assembled) and conspired to leave our car with a big, empty hole where the fuel cell should be three days before our next race.

In short: We were screwed, and there was no way we’d get the car done in time for Friday’s race.

Unless we used Racer Math, that is.

And remember, Schultz is run by racers. That’s why, astonishingly, Rob showed up on our doorstep, tank in hand, by lunchtime Tuesday.

He’d dropped everything and driven straight over, then vowed to spend the day helping us install it.

“I had the guys just tack the brackets in place rather than finish-weld them, so we can make adjustments way faster if we need to tweak anything.”

Shockingly, the tank fit first try–no adjustments needed–and bolted right up to the factory holes. Rather than add 1.5 hours of driving to take it back and weld it, Rob then set up camp in the corner of our shop, taught himself how to use our welder, and started TIGing up the final tank mounts right there in front of us. Racer Math!

By 9 p.m., Rob was still in our shop refining the filler neck design, which morphed from a simple off-the-shelf part to a custom-fabricated aluminum neck that would move the gas cap well out of our rearview mirror’s field of vision.

Finally, as the clock neared 10 p.m., the cell was done. Final capacity: 17.25 gallons, along with some bonus fuel in that big filler neck. Our Miata would finally be competitive.

Once we passed tech, that is.

Photograph by Tom Suddard

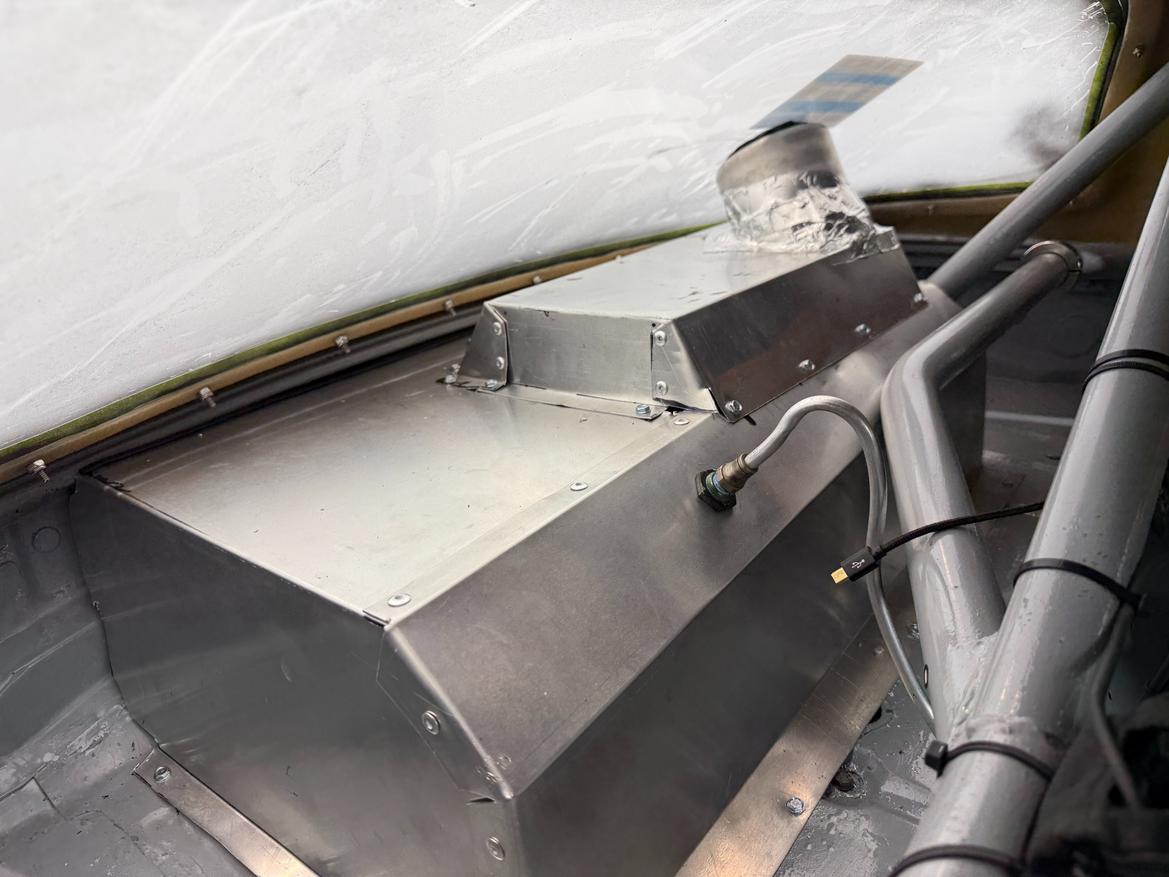

Our next mission? Build a metal firewall that completely separated the fuel system from the driver, meaning we still had a fair bit of fab work in our future.

To clarify, this firewall was absolutely not Rob’s problem. Schultz promised us a fuel cell; it was our job to integrate it into the car.

But Rob was having fun and wanted to make sure we made it, so he again dropped everything and showed up the next day to keep working.

We were all in the shop past 1 in the morning, finally putting down our tools when the car was ready to roll onto the trailer.

We’d done it.

And we should note that Tim Suddard, our founder, was right there working alongside us, too, and we couldn’t have done it without his help.

We’ll admit to having some rough edges to clean up–we didn’t realize our first cuts would be our final ones–but we think the final result speaks for itself.

Photograph by Tom Suddard

Our Miata now carries a competitive amount of fuel in a really safe, cleanly integrated, easy-to-install way.

Almost anyone with a Sawzall and a few hours of spare time could replicate this in their home garage. You won’t even need to make your own firewall, as Rob went home and added our design to his catalog, too: You can buy the entire setup–cell, filler neck, pump, firewall and all–directly from Schultz and build your very own tanker Miata.

Photograph by Tom Suddard

We won’t get a cut or anything, but we will get the satisfaction of knowing we could help you make your car more competitive. At the time of writing, pricing for the cell starts at $2900, while another $550 will get you a machine-made version of our prototype firewall and filler neck.

What if you don’t have a Miata but want a similarly custom fuel cell? Schultz says it’ll do that, too, though pricing will obviously vary based on the scope of your project.

View all comments on the GRM forums

You'll need to log in to post.